Developing countries may not get the investments in low-carbon energy they need

LONDON, July 8, 2021

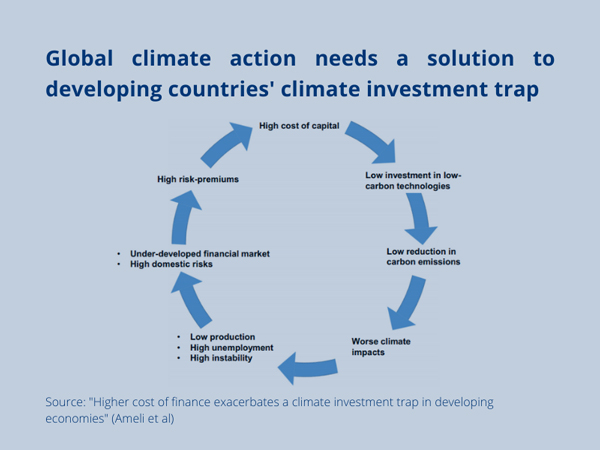

Sustainable finance is not doing enough to ensure that the need for low-carbon energy investment is matched with access to capital, and Net Zero in developing countries could be pushed back 5-10 years as a result of this ‘climate investment trap’.

A new report from University College London (UCL) shows how lack of financial market development in developing countries could perpetuate lower investment in low-carbon energy sources, which would lead to worse climate outcomes for these countries and perpetuate levels of international inequality that are incompatible with achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals.

The analysis from UCL shows how the assumption that an assumed equal weighted average cost of capital in most energy transition models assumes that more investment will be made to fund low-carbon energy in developing countries than is likely with real world financial market conditions.

To show the impact, the researchers compared outcomes for the European Union, where capital markets are highly developed and incentivised to support low-carbon energy, and African countries, where capital markets are more fragmented, with higher cost of capital and fewer incentives for investment in low-carbon energy projects.

The higher cost of capital in Africa than in the European Union (and broadly differences between developing countries and developed countries writ large) led to a delay in projected Net Zero energy in Africa from 2058 to 2065 and 20% higher forecast emissions in 2050. By contrast, policies that led to convergence of cost of capital by 2050 lead to 43% higher investment in low-carbon energy by 2050 than does the base case, where cost of capital remains divergent or converges only by the end of the century.

These different long-term paths of capital cost matter most for those living in developing countries, but it is not only their loss. Climate change is a global problem and every additional ton of greenhouse gas emissions has to be either reduced somewhere else or it will compound the impacts of climate change in every country.

The impact of higher financing costs in developing countries drives more investment in GHG-emitting energy to meet energy demand, as well as because carbon-intensive energy is less capital-intensive to install compared to low-carbon energy, which has very low marginal costs for energy generation. As the authors explain, the difference between Europe and Africa as representative examples of developed and developing regions is that: “While Europe aims to be the first climate-neutral bloc in the world by 2050, Africa faces rapidly rising energy demand and must leapfrog the use of fossil fuels to meet this demand, and instead deploy clean energy sources if climate targets are to be met.”

Lower than expected low-carbon energy installed in developing countries will have an impact on developed countries as well. It raises their level of investment needed to meet global goals. If fundamental cost drivers of low-carbon energy make the most cost-effective pathway to global Net Zero one that includes significant investment in low-carbon energy in developing countries, and financial market development impedes this, there needs to be an effort to find a solution.

One way to do this is to continue to expand catalytic finance such as blended finance, investment guarantees and capacity building to support financial market development and drive cost savings for the transition from private investors, the public sector and national and multilateral development banks. However, it is unlikely that each of the efforts needed will occur on its own without coordination of some kind.

The cost of the catalytic finance that is needed will be borne directly by those providing it while the benefits will accrue far beyond. This re-emphasises the critical role of the diverse types of financial institutions (public, private, and multilateral) in collaborating to address gaps or accelerate action to narrow the divergence in cost of capital for low-carbon energy projects in developed and developing countries, as well as between low- and high-carbon energy projects within each.

One factor that the researchers at UCL identify in perpetuating the financing cost gap is the current (developed country) sustainable finance ecosystem, and practices such as ESG screening.

These approaches lead multinational enterprises and investors from developed countries to invest more in low-carbon energy in markets where capital for such projects is abundant and less where it is scarce.

The ideal scenario that would contribute to a narrowing of the cost of capital for low-carbon projects would be the reverse.

The authors point to three other reasons for this systemic issue that are more due to sustainable finance frameworks and implementation, which impacts investors and MNEs’ decisions when they have a presence in both developed and developing regions:

*Investors often face a home-country bias in their investments, which leads to more investment in countries with ample capital available and developed financial markets and less in countries with more need for capital and less developed financial markets;

*ESG criteria tend to penalise countries “characterised by low democratic, transparency, human rights, and ethical standards, where such criteria are difficult to apply”; and,

*“Approaches focusing on financial risk show high climate-related financial risks in regions that are highly exposed to the physical impacts of climate change—especially if those areas have little capacity to prevent or adapt—and in regions that are carbon-intensive, as a result of expected asset stranding. Consequently, these high-risk regions are left aside by most investors, despite being, again, the most in need of investment.”

The key point to recognise is that there is a role for every part of the financial sector in addressing the financing shortfall for low-carbon investment in developing countries. Asset owners in developed countries should build capacity to invest in developing countries and avoid home-country bias. Asset owners in developing countries should collaborate to build capacity with developed market asset owners.

Meanwhile, both governments and financial institutions can evaluate the impact of their policies on ‘green taxonomy’, or ESG, to identify where it might create the unintended consequence of depriving capital for low-carbon investment where it is most needed. Responsible finance includes many universal principles, but it is not always implemented inclusively. This can have real-world consequences for everybody when it touches on issues of global urgency such as climate change.

-- TradeArabia News Service